One of the things guitar builders worry about is grain direction. It’s generally agreed that quarter-sawn wood is the most stable, or at least that it moves in a predictable, uniform way when the relative humidity changes. It seems to bend more easily, without breaks, than flat-sawn wood (I prefer quarter-sawn sides and bindings for that reason). And everyone agrees that it is stiffer than flat-sawn timber.

One of the things guitar builders worry about is grain direction. It’s generally agreed that quarter-sawn wood is the most stable, or at least that it moves in a predictable, uniform way when the relative humidity changes. It seems to bend more easily, without breaks, than flat-sawn wood (I prefer quarter-sawn sides and bindings for that reason). And everyone agrees that it is stiffer than flat-sawn timber.

After handling quite a bit of brace wood, I began to question that last assumption.

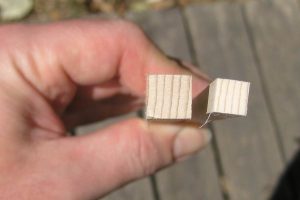

While cutting braces for the pair of orchestra model guitars I’m currently building, I squared up some leftover pieces to test whether grain direction affects stiffness. I was sort of scientific-ish about it; I didn’t run 300 test pieces to make it a proper study or anything, but I did have fun.

While cutting braces for the pair of orchestra model guitars I’m currently building, I squared up some leftover pieces to test whether grain direction affects stiffness. I was sort of scientific-ish about it; I didn’t run 300 test pieces to make it a proper study or anything, but I did have fun.

The squared stock needed to be accurately thicknessed in both dimensions and well quartered. I cut two pieces 16″ long and supported the ends, leaving a free span of 14″. I used the widely accepted standard weight, a one rubber mallet unit, tied to a piece of string looped over the center of the free span. Then I set up a dial gauge to measure the deflection from at-rest to under-mallet-stress and came up with the figures in the chart below.

| Size | Quarter-sawn Deflection | Flat-sawn Deflection |

|---|---|---|

| .372″ square | .018″ | .018″ |

| .237″ square | .086″ | .089″ |

Huh. It doesn’t seem that the quarter-sawn direction resisted deflection better than the flat-sawn direction.

Does this mean I’m going to stop carefully quartering my brace stock? Probably not. There could be other reasons that quarter-sawn braces prove better in the long haul. Maybe they resist splitting better, don’t deform over time, or resist becoming more or less convex as the humidity changes.

I’m also curious how runout and grain count affect stiffness, so look for tests of those characteristics in the future.